BACK TO RESEARCH WITH IMPACT: FNR HIGHLIGHTS

Access to essential health services is considered normal in high-income countries, while they are out of reach for many in low-income countries – gaps allowing preventable diseases to spread on a global scale. Field epidemiologists are working to understand what works in global health and how to improve public health responses to ensure equal health.

Global health research has paved the way for significant progress in areas ranging from rapid tuberculosis and HIV diagnostics to improved vaccine delivery in hard-to-reach areas. These advances underline the crucial role implementation research thereby plays in identifying what works, where, and why.

“In countries like Rwanda and Malawi, e.g., it supported the scale-up of community-based HIV prevention and treatment, substantially reducing new infections and disease mortality. In Ethiopia, it informed last-mile strategies that improved childhood vaccination rates, reducing or even avoiding disease outbreaks. If effectively bridging policy and practice, implementation research can foster smarter, more effective global and public health action,” explains Luxembourg national Nadine Muller, field epidemiologist, clinician scientist and medical doctor.

Understanding what works in global health

In high-income countries it is often taken as a matter of course – even taken for granted – to have access to essential health services: Vaccinations, antenatal care, treatment for tuberculosis or HIV, to name a few examples of important health services that are often not available in low-income settings.

“In Madagascar, one of my focus countries, around 1 in 3 children – nearly one million – have never received any routine vaccine, and 4 in 10 people with tuberculosis (TB) – about 10,000 annually – remain undiagnosed or untreated. These gaps allow preventable diseases like measles, polio, and TB to spread globally. My research at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin focuses on understanding what works in global health, how to improve public health responses, and how barriers can be overcome to ensure equitable healthcare for all.”

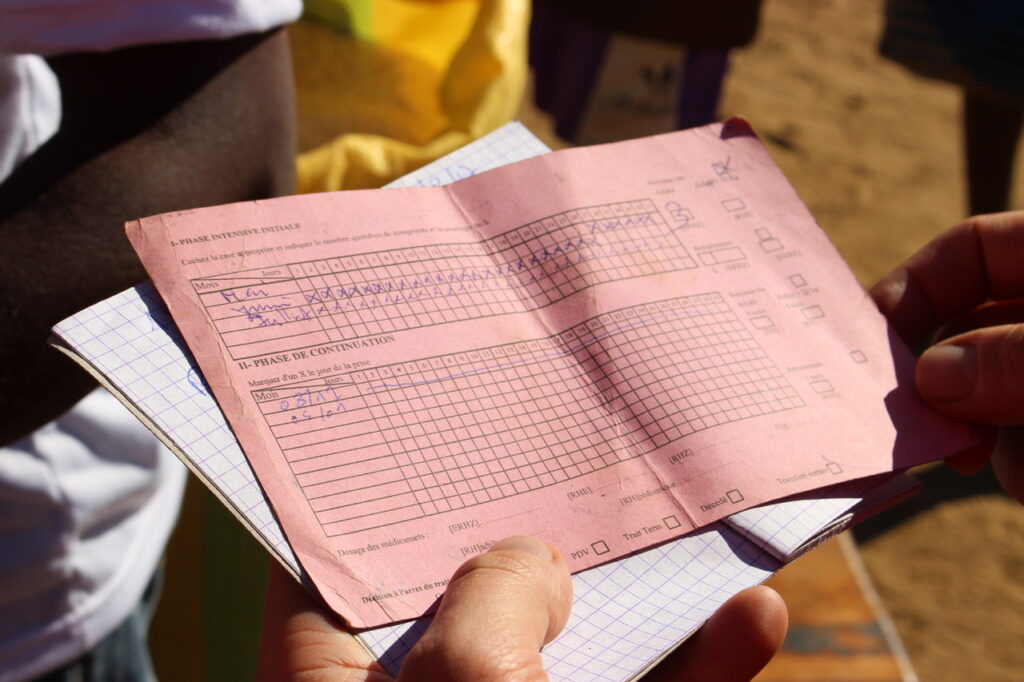

A healthcare worker of a mobile TB clinic prepares samples in an empty classroom. Research shows these clinics are a highly cost-effective way to expand TB care in underserved areas.

Samples collected at a mobile TB clinic. Research shows these clinics are a cost-effective way to expand TB care in underserved areas.

Focus on where services meet communities and frontline workers

Nadine’s research is focused on healthcare delivery at the “last mile”, meaning where services meet communities and frontline healthcare workers. Together with local and national partners, exploring the factors enabling or obstructing access and quality of care. The goal: to identify effective, scalable solutions.

“We prioritise making our findings actionable for policymakers and practitioners. At the same time, we critically examine the dynamics of Global North–South partnerships, advocating for more equitable, respectful collaboration. Strengthening mutual learning and shared ownership is not only an ethical imperative but also essential for building sustainable systems and advancing health equity in diverse, real-world settings. ”Nadine Muller Field epidemiologist, clinician scientist and medical doctor

Together with her team, Nadine has for example conducted an impact and cost-effectiveness analysis of a low-tech mobile clinics approach. The analysis was clear about how many funds are needed for each patient treated and “each health live reached in a setting where evidence is largely lacking towards effectively scaling. This analysis substantially helps organizations and funders in choosing their approach and planning effectively towards expansion and scale.”

Collaboration across sectors essential for real change

Nadine explains that it represents a significant challenge that research is often seen as separate from public or global health action and that the idea that researchers are only meant to inform policymakers is outdated.

“To drive real change, we must actively collaborate across sectors, engaging with governments, civil society, and the private sector, to make evidence accessible, relevant, and usable for those shaping policy and public health measures.”

What stands in the way of solving this challenge is not a lack of knowledge or ideas on how to solve particular questions, Nadine explains, but a combination of limited collaboration and weak mechanisms to translate evidence into action.

“Complex health systems, political interests, and fragmented funding further slow progress. Research must be better integrated with practice through trust, dialogue, and shared ownership across all actors involved.”

Nadine MULLER, MD, MSc is a medical doctor & field epidemiologist currently working as a Clinician Scientist at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the Centre Global Health.

MORE ABOUT NADINE MULLER

Describing her research in one sentence

“My research explores how to make essential health services, such as vaccinations and HIV and TB diagnostics and treatment, more accessible and effective in underserved communities by identifying what works, why it works, and how it can be scaled up fairly and sustainably.”

Working as a clinician scientist

“As a clinician scientist, working in both clinical medicine and research – and across different settings – enriches my work in both fields by allowing me to draw from a broad range of perspectives. I choose to work in academia as it gives me the freedom to design and act independently while being in an international environment of massive expertise.”

What she loves about research

“I do love that the research I do, if conceived well, which means focused on real needs, adapted to local contexts, and in close collaboration with local stakeholders can have a big impact on communities and global and public health. That’s what motivates me most – actively and effectively contributing to making access to quality health services more equitable.”

Mentors with an impact

“Yes! I’ve been fortunate to be mentored by Beate Kampmann and Leif Sander, both of whom have broad expertise and provide supportive guidance as needed. Having them as trusted colleagues during challenges is invaluable – I rarely need to reinvent the wheel.”

Where she sees herself in 5 years

“In a cross-sectoral international health domain where I can continue to contribute to impactful initiatives.”

Related highlights

Spotlight on Young Researchers: Smarter choices for complex systems

Complex systems are part of our everyday lives: smart cars, satellites, medical devices – but if they fail it can…

Read more

Spotlight on Young Researchers: Modelling Forest survival in a changing climate

Forests are dynamic ecosystems – they are used to change but it takes time to adapt. Climate change means drastic…

Read more

Spotlight on Young Researchers: Ensuring sustainable water use for Luxembourg

In Luxembourg, nearly one tenth of water consumption happens in agriculture. Changing rainfall patterns and rising irrigation needs during summer…

Read more

Spotlight on Young Researchers – Revisited: From researcher to project manager

When Xianqing Mao was featured in Spotlight on Young Researchers in 2017, she had completed her medical degree and was…

Read more

Spotlight on Young Researchers: Giving robots a more human touch

The use of robots is rising, both in industry and in homes. This is made possible by scientists leveraging artificial…

Read more

Spotlight on Young Researchers: Cancer in older people & the need for a tailored approach

Cancer in adults aged 65+ is increasing, raising pressure on healthcare systems worldwide, creating economic and social burdens for families…

Read more